Jay Caspian Kang gave us an article in the June 23rd issue of The New Yorker that unites several of his beats: education; social mobility; and hoops (it’s called Heir Ball). The article concerns a trend of greater segregation by talent or wealth in elite youth basketball formation. Think: Extravagantly well-resourced private academies of NBA hopefuls. These boys themselves are also frequently to the manor born, both as a matter of financial and genetic assets. They are not just very tall; they are the very tall children of NBA players.

Kang raises the question of whether the professional basketball game is the worse for this. The theory of decline relevant to us here is the idea that there is value in the formation by fire as a young person playing against older players in a pickup scene. Basketball veterans voice concern to Kang about what is lost with the end of the era of learning “outside.” (“Outside” is shorthand for pickup games with older boys.) Outside is what players up to, say, the LeBron era often started with. The concern goes that the current deliberate cultivation system leads to weaker, cookie cutter skills and less ability to creatively improvise and direct one’s own, creatively unique game.

Here’s another morsel that encapsulates the potentially perverse consequences of treating the highest tier of teen basketball players like say, gymnasts of equivalent potential.

One coach told the authors of the report published by Luka Dončić’s foundation, “Players don’t know how to anticipate where the ball will fall because they’re so used to their trainers getting their rebounds.”

If that anecdote weren’t real, the researchers and pundits concerned with the coddling of the American mind-body would have to invent it to encapsulate their message.

Kang’s article made me reflect more than I ever had on the fact that I was brought up a bit over 1,000 feet from two unavoidable pickup scenes.

One was a basketball court at West 4th known for aggressive play. Some speculate this style of play has to do with the court being smaller than regulation (which could also be extended to explain the Manhattan apartment-dweller personality type). The place is called “The Cage,” though it’s not the sort of name that I’d heard people using. I walked past it every day on the way to and back from school up Sixth Avenue. I don’t recall ever seeing children or women play there.

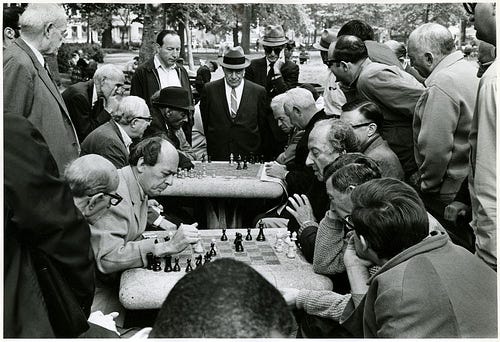

The other pickup community in my minuscule orbit was not basketball, but rather a chess scene inside Washington Square Park, southwest corner. The place boasted fixed tables with concrete slab tops inlaid with chessboards. To the wider public, it was known for intense play, but also hustlers. To a small child like me whose life revolved around that particular corner of the park, it was merely another group of unpredictable male strangers to carefully avoid. It was similar to how we avoided discarded drug paraphernalia or adults occupying the wooden adventure playground structure beside the 3 “hills” play feature that children more confidently claimed.

So: chess and basketball are two scenes that have long since been associated with the idea of “free for all” in my mind. Since I was a girl, and these spaces were decidedly not girl-centric, I wasn’t what you’d call curious to learn more at the time. But now that I know more, that association has been amended to “free for all for learning, under the right circumstances.”

So, where does a pick-up-curious parent given to experimentalism begin? Basketball is certainly a sport my children love watching, and pickup games sound fun to observe. Nonetheless, our kids have never played basketball more than at an occasional recess. So there is no urgency to the idea of dropping our rising third grader and kindergartener off at an Oakland park to play until sundown with aspiring Jason Kidds. Some day, perhaps.

The kids do play chess now, though. Up until now, it’s been in classes or at home with patient adults catering to them. OR, and let me stress this is the VAST majority of their play time: With digital “coaches” or “opponents.” The likes of Kahoot/DragonBox’s chess app and DuoLingo’s chess course, which are both well done. Or some of the easier bots on Chess.com. (Soon we’ll decide if we’ll expose them to other adults on platforms like Chess.com. On the Internet, nobody knows you still have all your baby teeth.)

After Kang’s piece, though, it made me think that it might be time to hasten the kids’ exposure to pick-up scenes where they are the worst and youngest, and no adult is in charge or obligated to facilitate their individual experiences. We had recently tried the library chess club, but, perhaps by design, it was all very young children and some were complete beginners. Parents were there and actively helping some of the children and praising my kid quite a bit. None of that is bad (and we’ll continue to enjoy it occasionally); but it’s somewhat similar to what the kids get at home.

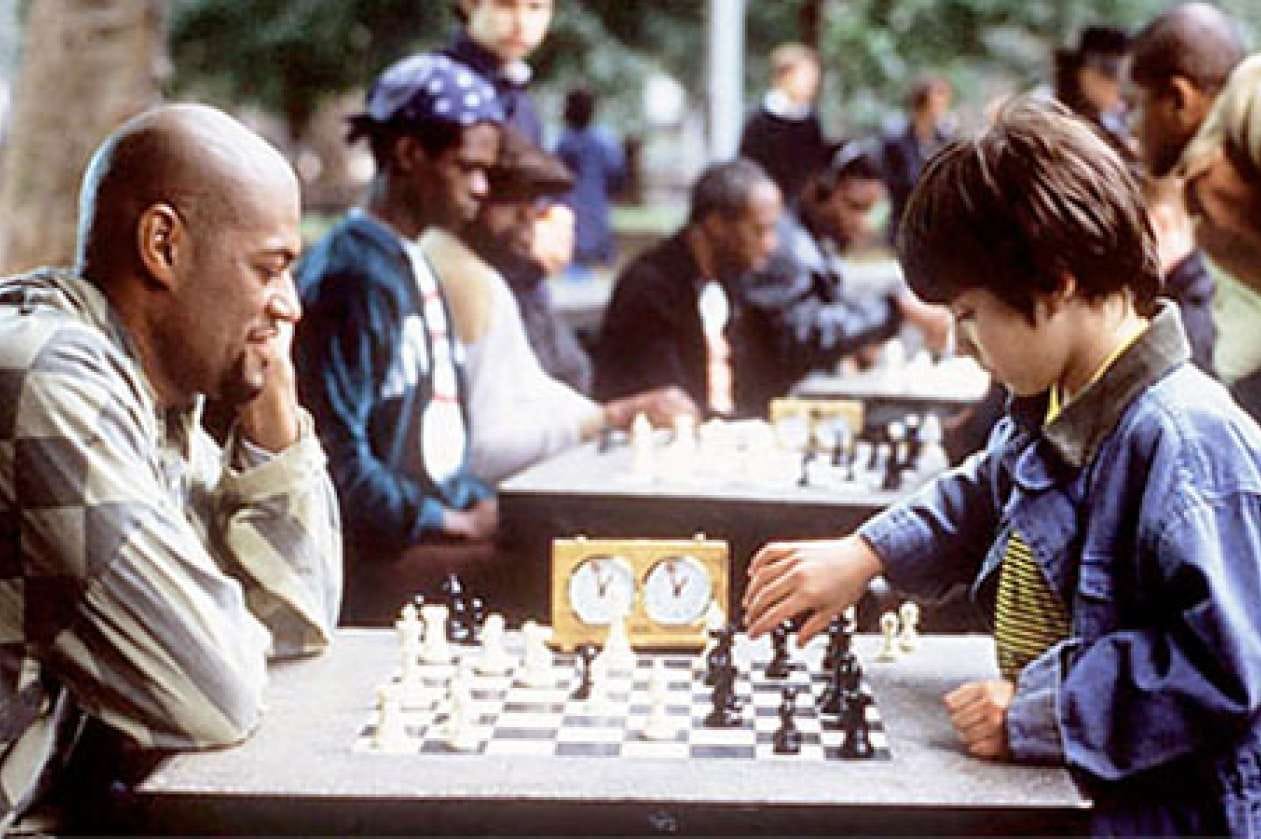

As it happens, many small boys and girls also grew up with their mamas walking them through the Washington Square chess scene. For one boy in the neighborhood, a few years older than me, something unusual happened. His parents decided to have this boy play in the pickup scene there at age six. AND (a big “and”!) the boy was holding quite the genetic lottery ticket.

The child’s name was Joshua Waitzkin, and he played chess with success for a time, becoming an “International Master” in his teens. They made the movie Searching for Bobby Fisher about Waitzkin, based on a memoir by his father about raising a chess Grandmaster hopeful.1

Waitzkin took some unconventional directions in his life. He quit elite chess after college, and before to long became a world champion Tai Chi competitor. Then he turned to jiu jitsu, becoming a black belt. Now he is an expert at large on learning in the popular “peak performance” space (for those unfamiliar: it’s like the skincare internet community, but for men interested in excellence per se).

Why do I bring Waitzkin up? It has to do with the reason I discovered he gave about why he left chess: A lack of “love.”

When people ask me why I stopped playing chess ... I tend to say that I lost the love. And I guess if I were to be a little bit more true, I would say that I became separated from my love; I became alienated from chess somewhat ... The need that I felt to win, to win, to win all the time, as opposed to the freedom to explore the art more and more deeply, and I think that started to move me away from the game and also chess for me was so intimate. It was something that I loved so deeply that when I started to become alienated from it, I couldn't do it in an impure way.

Here is part of Waitzkin’s mission statement online for his current career, :

By exploring themselves more deeply, and unearthing and internalizing nonlocal principles that connect their arts to others, elite performers and artists transform their journeys to virtuosity by amplifying what makes them unique (what Josh calls their “funk”) [emphasis added], generating their own training ecosystems, and harnessing the power of thematic interconnectedness.

This person majored in philosophy, so creating a personalized term of art in “funk” may not have been done lightly; nor the decision to capitalize the word Quality each time it appears on his website.

So, why I bring Waitzkin up: When I think about aspirations for parenting, one is to give kids a chance to become a person who has the strength to walk away from something they are rewarded for because they don’t love it. Another is to give kids a chance to become the sort of person who invents their own terms of art, like “funk,” because they are so excited about their ideas they want to give them names, as parents do their babies. Even if I don’t like those ideas!

And, it is plausible to me if that pickup chess games “outside” (like the NBA oldheads describe their formation) in Washington Square may have been some part of the ingredient in Waitzkin’s confidence in following his own “funk.” Rather, than, say, becoming a by-the-book player executing moves estimated by experts and their software to improve winning odds for a similarly situated player—in chess or in basketball.2

After I found out about Waitzkin yesterday, I looked into whether there is a belief held by chess experts that coming up in “outside” chess confers any specific value. And yes, there is a view out there that it is helpful to learn against outsiders and hustlers. For example, because they play unexpected patterns. In fact, Waitzkin himself says something to this effect on his website. My guess is you’d find a similar belief among some experts in most fields of training or study. Even speculative fiction about what it takes to be a starship captain (a maverick’s intuition and spontaneity!).

And, well, well, well, look who the internet says Waitzkin has been consulting for: The Boston Celtics head coach Joe Mazzulla. If you find yourself with Gen Z players who never played street ball, perhaps it takes need a street chess veteran to help them find their… funk.

Until this very day, I thought that movie was about Bobby Fisher. Now I plan to watch it!

Makes me think of the moment in Chernobyl when a scientists suggests using “bio-robots” (young men) to clear radioactive debris when true robots prove hard to come by.