How to Give a Child The Little Prince

And a charming doll and miniature book to go with it!

Buying children’s classics is more laborious than buying new releases or vintage books that exist in only a couple of editions. One is tired out by the number of decisions to make about book design, vintage, craftsmanship—not to mention which translation or illustrator to select.

Perhaps that’s why ones shelves often contain a fair number of random, unsatisfactory copies of classics. Copies that do nothing to convince a child to give the less than completely fashionable a chance. The silver lining is that these hurdles are why something from the children’s canon can be such an excellent gift.

I’ll start with The Little Prince, because I dote on a boy whose hair reminds me of a wheat field.

If the child doesn’t read French, then the first consideration is which translation.

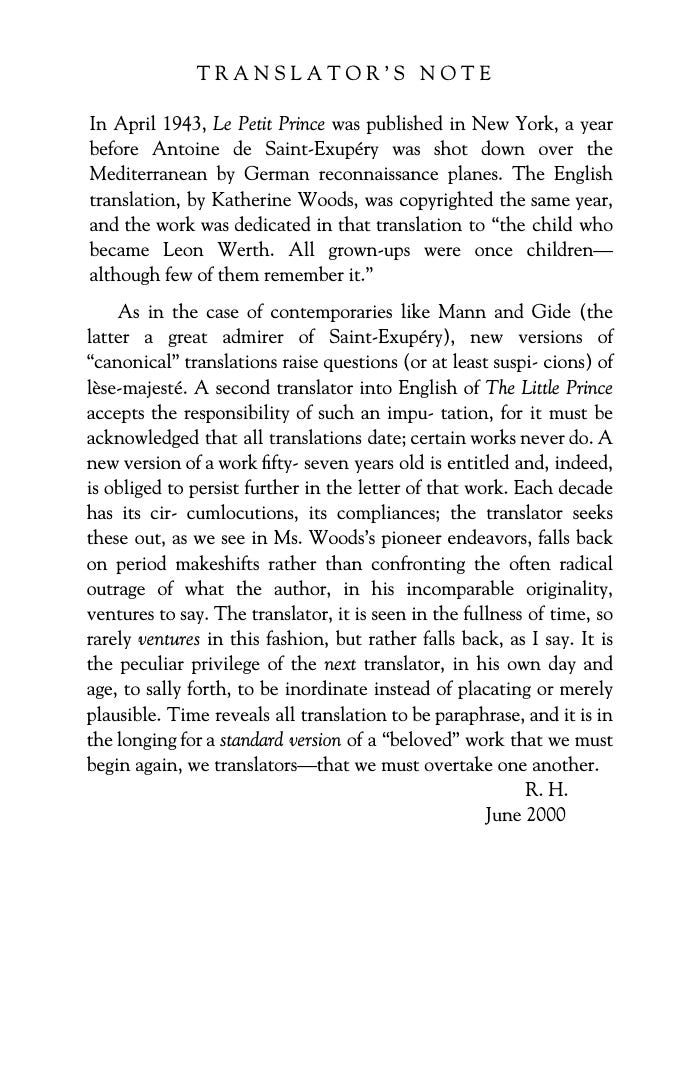

The main circulating English version of The Little Prince now is by the late poet Richard Howard. His version unseated the original by Katherine Woods. Howard’s work is considered by some more faithful to Saint-Exupéry’s simple, accessible prose, and is viewed by admirers as less stiff. (Also, Woods’s translation has one of the most famous translation errors.) By others, Howard’s translation is viewed as a failed assassination attempt. Howard foresaw this:

Katherine Woods’s translation is particularly dear to many as it came out alongside the original French text in 1943. Saint-Exupéry (Saint-Ex) had written the work in New York while in exile from occupied France. Both French and English editions were published in New York. (They were not published in France until after the war, by Gallimard.) The Woods translation remained the standard for half a century in the English-speaking world. Her reign was coextensive with the book’s exuberant reception by anglophone audiences and its eventual canonization among English-language classics.

How you feel about the Woods vs. Howard controversy may turn in part on how you feel about the following comparison, made by another Francophone American writer, Matt Kim:

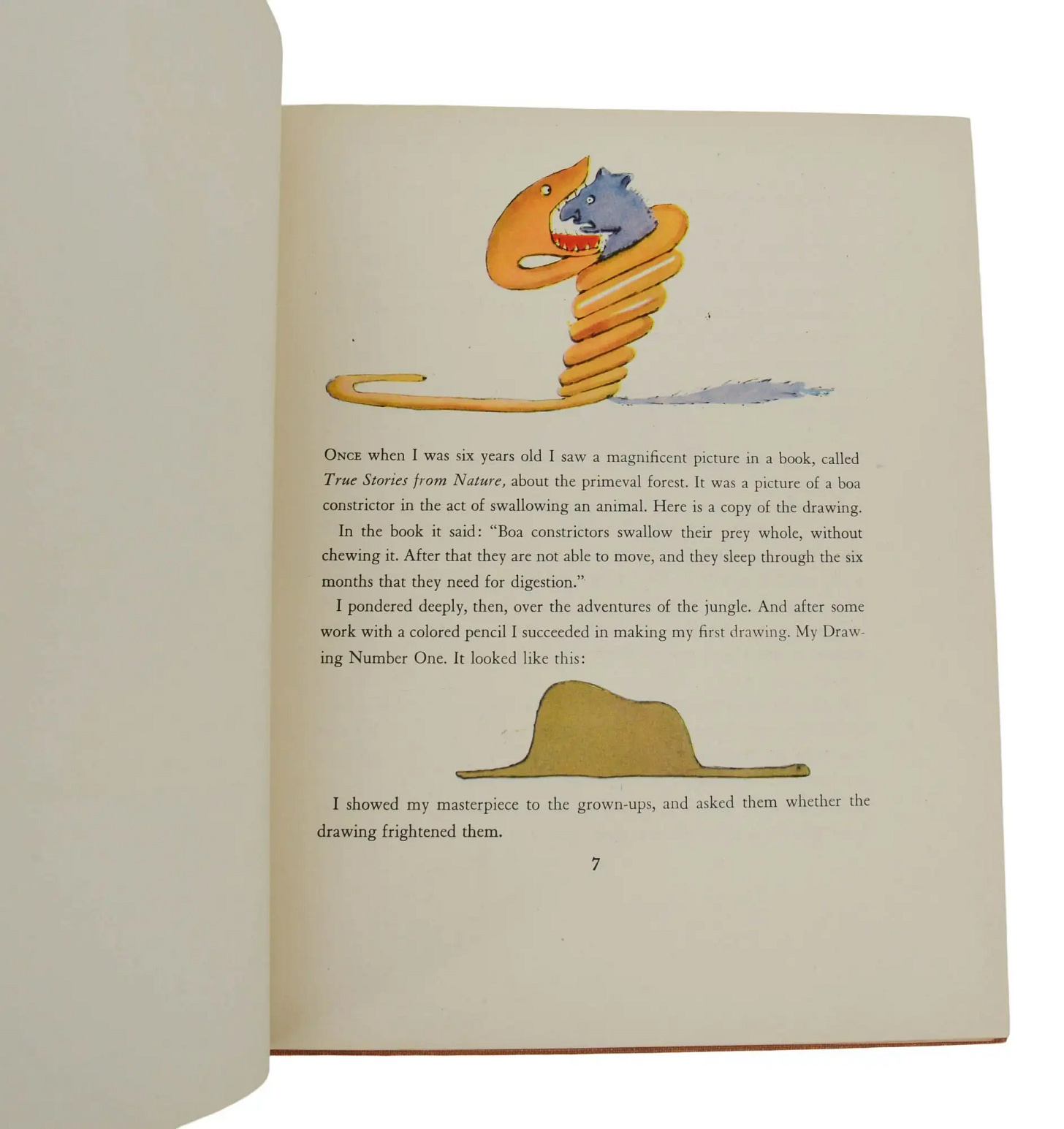

Woods’s version includes French-to-English translations like “spring of fresh water”, “primeval forest”, and “tippler”. Howard translates the same words as, “water fountain”, “jungle”, and “drunkard”.

But the story of Woods’s romantic flourishes vs. Howard’s straightforward choices is not the only one that can be told (even in this example, we have drunkard, rather than drinker). If you’d like more raw material to understand how the two versions sit on your palate, here is how Woods and Howard interpreted the closing paragraph of the book’s first chapter:

The French original:

Quand j’en rencontrais une [une grande personne] qui me paraissait un peu lucide, je faisais l’expérience sur elle de mon dessin numéro 1 j’ai toujours conservé. Je voulais savoir se elle était vraiment compréhensive. Mais toujours elle me répondait : «c’est un chapeau». Alors je ne lui parlais ni de serpents boas, ni de forêts vierges, ni d’étoiles. Je me mettais à sa portée. Je luis parlais de bridge, de gold, de politique et de cravates. Et la grande personne était bien contente de connaître un homme aussi raisonnable.

Woods (1943)

Whenever I met one of them [a grown-up] who seemed to me at all clear-sighted, I tried the experiment of showing him my Drawing Number One, which I have always kept. I would try to find out, so, if this was a person of true understanding. But, whoever it was, he, or she, would always say: “That is a hat.” Then I would never talk to that person about boa constrictors, or primeval forests, or stars. I would bring myself down to his level. I would talk to him about bridge, and golf, and politics, and neckties. And the grown-up would be greatly pleased to have met such a sensible man.

Howard (2000)

Whenever I encountered a grown-up who seemed to me at all enlightened, I would experiment on him with my drawing Number One, which I have always kept. I wanted to see if he really understood anything. But he would always answer, “That’s a hat.” Then I wouldn’t talk about boa constrictors or jungles or stars. I would put myself on his level and talk about bridge and golf and politics and neckties. And my grown-up was glad to know such a reasonable person.

Primeval forest vs. jungle (for forêt vierge)? Clear-sighted vs. enlightened (for lucide)? Should one raise Woodists or Howardists?

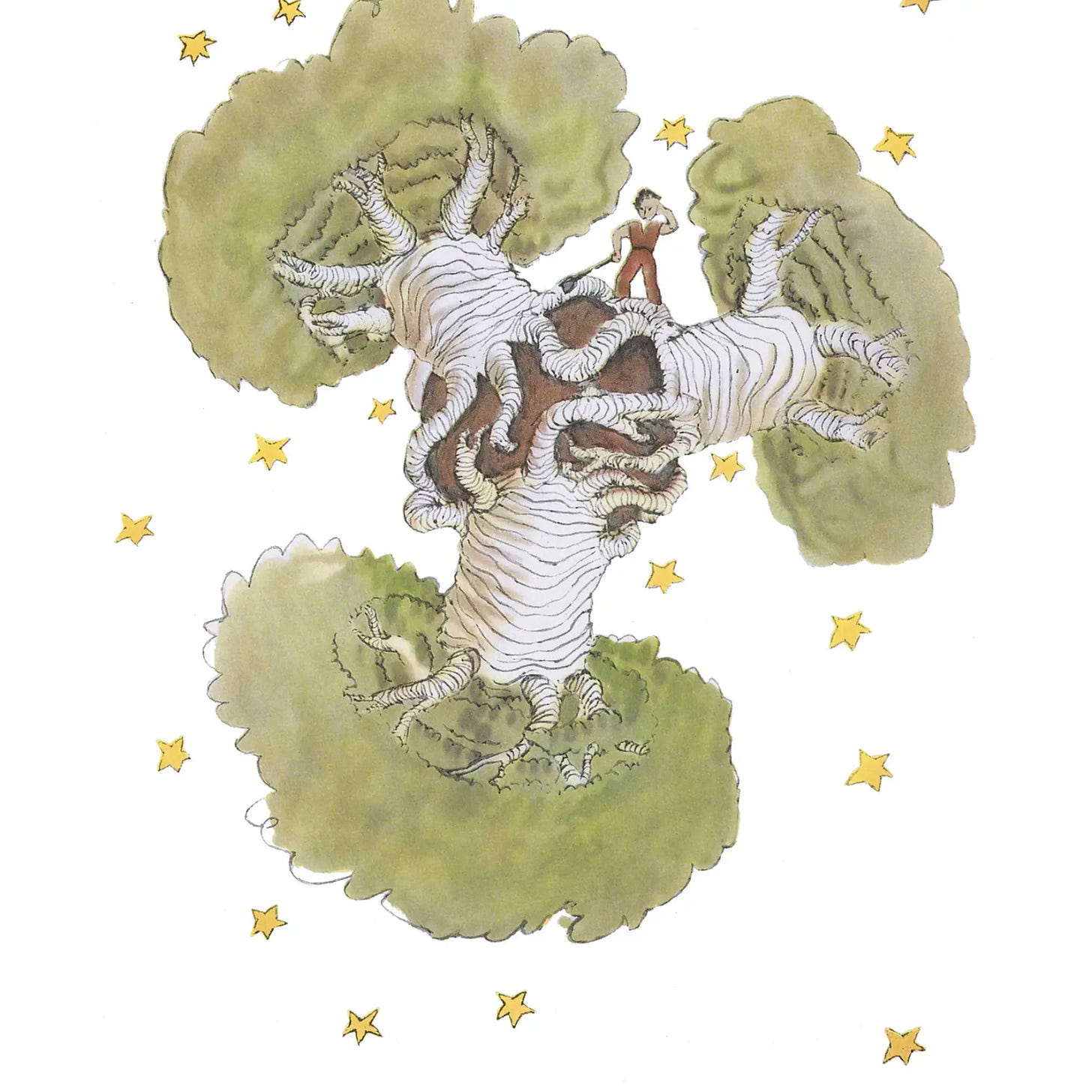

My own nostalgia for Woods’s translation notwithstanding, my recommendation would be “both,” because The Little Prince is an excellent candidate to be a child’s introduction to translation itself. You might begin with a discussion of how to translate fauve, the poor creature staring into the jaws of death in the book’s memorable opening page. Fauve has no direct analog in English; it is rendered as “animal" for Woods, “wild beast” for Howard, and even “wildcat” from the default Kindle Edition we downloaded.1) « Le langage est source de malentendus », as the fox counsels the little prince.

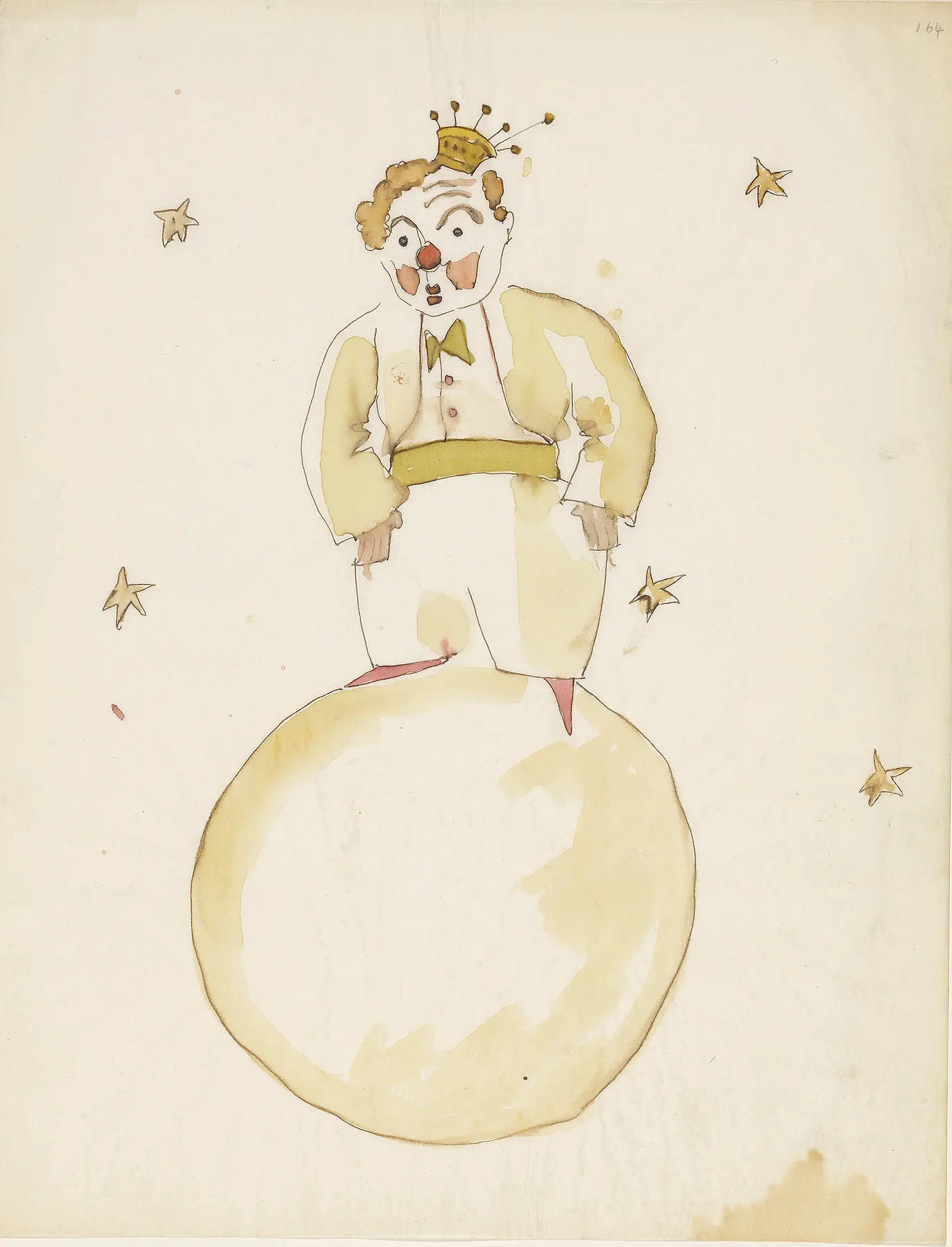

Then there’s the question of how best to enjoy the author’s illustrations. For a copy with strong reproductions, I recommend the Folio Society release, which aimed to restore faithfulness to the original colors. The Folio Society release also includes a commentary volume from former Morgan Library curator Christine Nelson, who took care of the Little Prince manuscripts for several decades. This companion volume includes reproductions of parts of Saint-Ex’s handwritten drafts and preliminary sketches.

The Folio Society used the Richard Howard translation. So it pairs well as a gift with a vintage copy of Katherine Woods’s now out-of-print translation. Here’s a guide to collecting first editions from the fabulously thorough Little Prince Swiss collector and general allumeur de réverbère Jean Marc Probst (his detailed collection site is worth perusing). Thanks to Probst, I now know that the first 1943 French editions, unlike the English, bear “the mark of the raven.”

Here’s a handsome early edition of The Little Prince for sale—lacking dust cover—at $1,250:

Less extravagant would be to buy a vintage copy from the later Harcourt era (Harcourt absorbed the original publisher, Reynal and Hitchock). Finding the Harcourt-era Katherine Woods translation is easier if you restrict the time period to before 2000, when Howard’s version was published (here’s a search).

Some further items to sweeten your gift or peruse at your leisure:

Gallimard sells a facsimile edition of the original manuscript (59€).

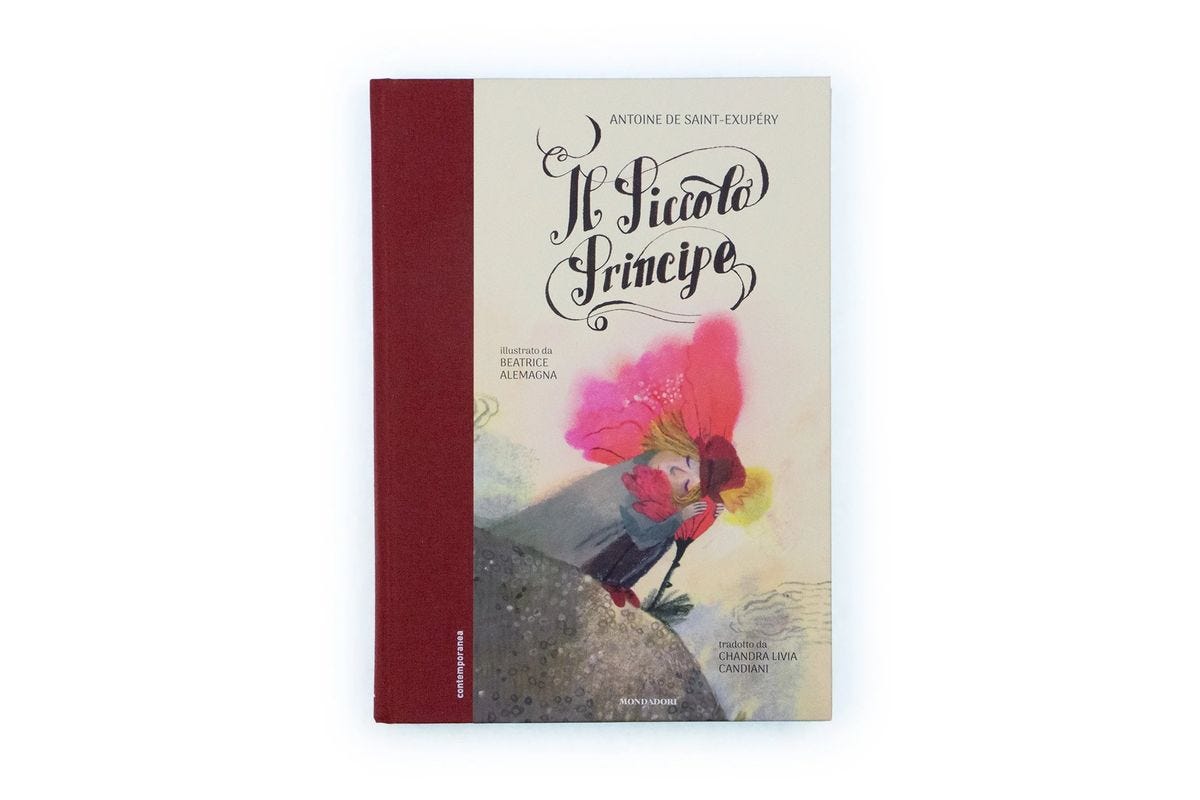

Over the years The Little Prince has been illustrated many times by new interpreters. Very few tempt me as a collector, but Probst created a nice gallery that will allow you to see if any “third party” illustrators catch your eye. I am an admirer of the Italian-born, France-based illustrator Beatrice Alemagna, and am partial to her edition.

A book is best given with a doll; and that doll in turn is best given with its own miniature book. Thanks to the cottage industry around The Little Prince, you have a lot of mini options for both a large companion like the Nanchen doll above, dollhouse scale, or in between. This miniature one looks to be the full-text Katherine Woods translation. This one is for recreating in the dollhouse your child’s grandparents’ mustiest shelves. I am against the ones with blank pages, as I’m sure will be the borrowers who live under your floorboards.

It is unlikely to be obvious to parents what editions of translated works their children are reading on their Kindles. The English Kindle Edition translation that downloaded for us by default was published in 2017 from Babelcube, a global translator outsourcing platform.

Fascinating! Never knew about this English translation drama. (I only had read the book in Spanish, and my daughter has it in Spanish as well.) Love the idea of giving the book with not only a doll, but with a miniature version of the book for said doll. Just perfect.